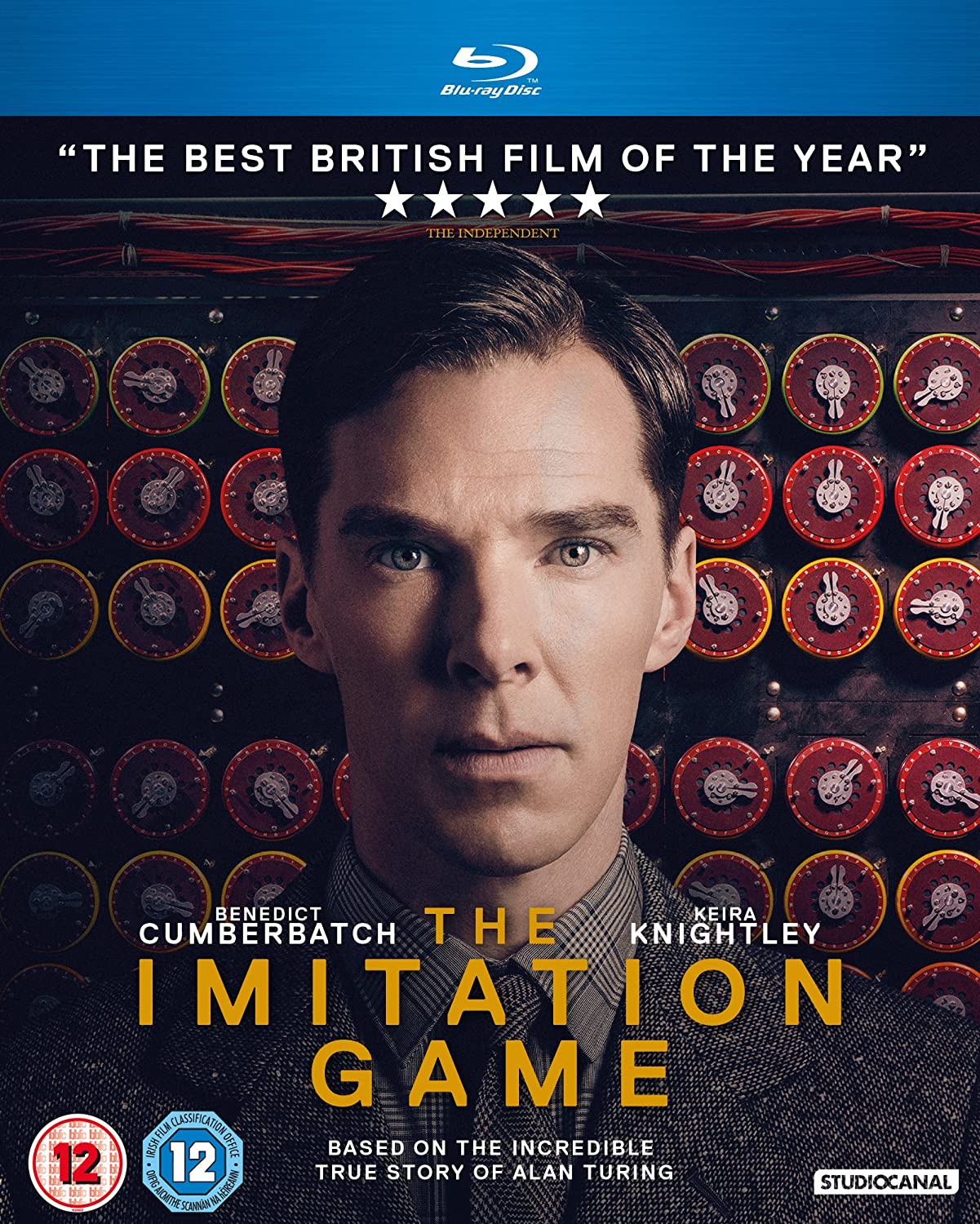

Inspired by this game, Turing devised a thought experiment in which one contestant was replaced by a computer. The judge had to guess who was who, but their task was complicated by the fact that the man was trying to imitate a woman. Instead of trying to define the terms “machine” and “think,” Turing outlines a different method for answering this question derived from a Victorian parlor amusement called the imitation game. The rules of the game stipulated that a man and a woman, in different rooms, would communicate with a judge via handwritten notes. In 1950, at the dawn of the digital age, Alan Turing published what was to be become his most well-known article, “ Computing Machinery and Intelligence,” in which he poses the question, “Can machines think?” While it can be exciting to be swept up by the idea of super-intelligent computers that have no need for human input, the true history of smart machines shows that our AI is only as good as we are.

In this six-part series, we explore that human history of AI-how innovators, thinkers, workers, and sometimes hucksters have created algorithms that can replicate human thought and behavior (or at least appear to).

What’s lost is the human element in the narrative, how intelligent machines are designed, trained, and powered by human minds and bodies. The history of AI is often told as the story of machines getting smarter over time.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)